Updated: 07/17/18 | July 17th, 2018

Though I’m terrified of flying, the experience also thrills me. There you are, cruising in a metal tube at 37,000 feet while watching a movie, texting your friends, and — if you’re a travel hacker (and you should be) — enjoying fine food and liquor.

I can never get over the fact that planes, which can weigh up to 485 tons and contain, like, up to 6 million parts, can even get into the air — and stay there! Yes, I know all about aerodynamics (“it’s just lift!”), but it’s still so damn cool!

So when I was invited to my first aviation press event at the end of March, I was beyond excited. I don’t get a lot of media invites since I don’t report on breaking industry news, but when I was asked if I wanted to tour the Boeing facility in Charleston, South Carolina, as part of Singapore Airlines’ 787-10 launch, I immediately said yes.

Watch a plane get built? Fly a flight simulator? Yes. Yes! YES!

At the Boeing plant, we were treated to tours of the Dreamliner assembly process. We went to the production facilities where, after a long and boring press conference on flight specs and fuel savings, we finally got to go down to the factory floor to see the good stuff. Walking on the floor and seeing these metal behemoths really gave me a sense of wonder and awe.

Like, “Damn, that’s a plane!”

Before this, I had only a rough idea of how planes are built, how engines work, and the complicated manufacturing process that’s required to put it all together. I mean, I’ve watched a few documentaries on flying. But unlike most of the other aviation press there, I couldn’t tell one plane or engine from another, discuss avionics or contracts between suppliers, or who designs what seat fabric.

So I was excited to learn about the factory assembly process and how a plane becomes a plane.

At the plant, there are three areas to the plant: rear body, midbody, and final assembly.

The rear body process is where the tail of the plane is made, and the Charleston plant makes all the tail sections for all the 787 Dreamliners (minus the fins). One thing I did know before this trip was that they use carbon fibers, which have several advantages over traditional composite metal, including high tensile strength, low weight, high chemical resistance, high-temperature tolerance, and low thermal expansion. Basically, they are stronger and lighter than traditional metal. They take a tacky composite carbon fiber tape and spin it together around a shell to make the tail sections, called Section 47, where the passengers are (Why Section 47? No one knows. There aren’t actually 47 sections to the plane. That’s just what they call it!), and Section 48, which is the very end of the plane, where the fins will be attached. It’s kind of cool to think about. When you fly a 787, you’re basically flying a plane that mostly started as a thread. Science, man, science!

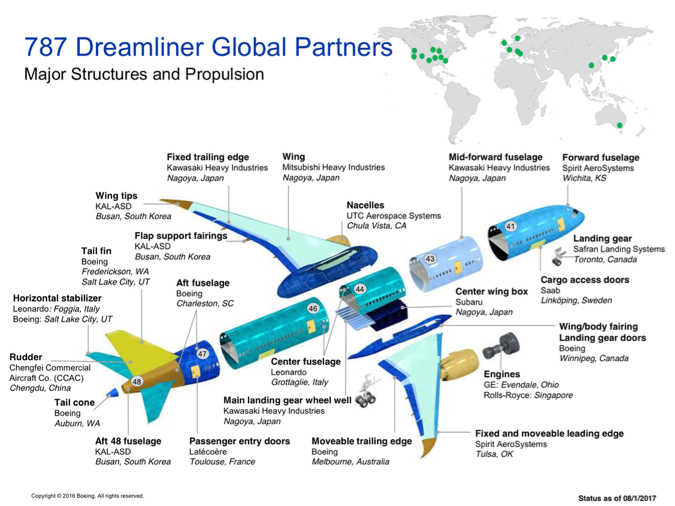

All the other parts of the plan are built elsewhere around the world and then flown in on this weird-looking plane called the Dreamlifter: part of the front of the body (called the forward fuselage) is built in Wichita, Kansas; another part of the forward fuselage is built in Kawasaki, Japan; the center fuselage is built in Alenia, Italy; and the wings are built in Japan, Oklahoma, and Australia. Here’s an image Boeing gave me to give ya an idea of how global Dreamliner production is:

During the midbody process, some of the electrical systems and ducts are added to the plane. They also “snap” together the fuselage sections that are flown in from around the world. Basically, there’s a thin lip in each of the sections, and a machine use fasteners to put them together, which is both exciting and considerably unnerving to see because you realize just how amazing it is that it takes so few parts and how few things are holding this places together. For example, they have just seven rivets that snap the wing to the plane (later, during final assembly) and hold all that weight. Nope, they aren’t welded together. It’s like an oversized Lego set!”

Watching them put the fuselage together this was the most interesting part of the plant didn’t allow photographs, which was a shame. But, since Sam Chui is a badass aviation blogger, they gave him access to film it, so watch this video:

From there, it’s on to final assembly where, over the course of seven stations, all the sections are lined up and put together using a “just in time” factory model. It’s here the wings and engines get put on, the interiors are added, the plane is turned on for the first time, systems are tested, and the finished aircraft is driven out of the hangar for test flights.

This final assembly takes approximately 83 days.

Kinda crazy, huh? You never realize just how much goes into a plane. It’s quite impressive that such a coordinated, global operation can produce such a finely tuned piece of machinery that can essentially fly forever with proper maintenance.

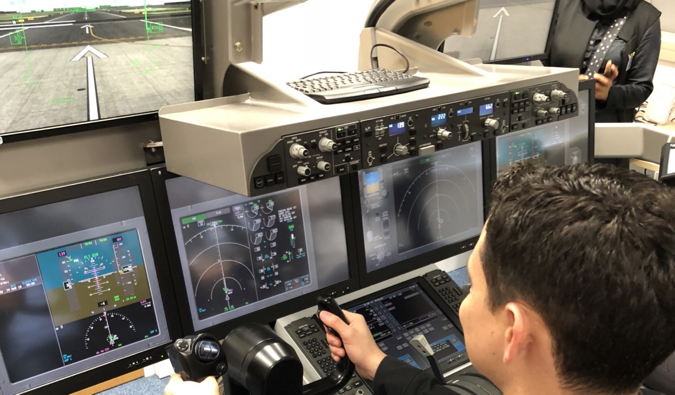

Then, after a 24 hour flight to Singapore, we were taken to where Singapore Airlines trains its crew in safety and service and, while I found it pretty interesting, the real fun was flying a 737 flight simulator back at the Boeing office in town. These multimillion-dollar machines simulate the full motion of a flight. After a brief demonstration, each journalist was allowed a few minutes to “fly.” I giddily sat down in the chair as the pilot let me cruise around for a bit.

I was like a kid in a candy store.

“Can I bank? Can I land? Let’s do a takeoff!” I exclaimed.

“If we have time, we can go again and I’ll release the autopilot,” the instructor coolly said after my thirty seconds was up.

Luckily, we did have time.

“Ready?” he asked as I stepped back into the seat.

“YES!”

We started in midair, he released the controls, and I flew around a simulation of Singapore for a bit.

“Not bad,” he said. “Ready to land?”

“Sure, but can we do a go-around?”

Taking the controls, I aborted my landing, turned up, and banked left so we could do one more circuit. Just as I was enjoying the bliss of the computer-generated scenery, I crashed!

I had forgotten to look at the screen and see my altitude, so while I thought I was just going left, I was actually banking down — and boom! We died.

I guess I won’t be a pilot anytime soon. There is a surprisingly large number of controls and numbers you need to pay attention to on a modern aircraft, especially when you release the autopilot!

Afterward, we got to go into another simulator that allowed pilots to practice takeoffs. It wasn’t a full-motion simulator, but it was designed to get you to take off and feel the movement of the controls.

This time, I successfully, took off and no one died. So you’re safe with me!

For a long time, I’ve been terrified of flying — and watching a plane get built and learning about aviation did nothing to assuage that fear. I’m still unnerved by every little bump (the flight I am currently writing this on has been nothing but bumps!), but I have a new appreciation for how complex and strong planes are, how many safety systems are built into them, how hard it is to fly one, and just how damn amazing it is we live in the age of jet travel!

Editor’s Note: I was a media guest of Singapore Airlines and Boeing for this event. They covered all my expenses during these press days.

The post How an Airline Plane is Built appeared first on Nomadic Matt's Travel Site.

from Nomadic Matt's Travel Site https://ift.tt/2uJVHhQ

No comments:

Post a Comment